29

мар

Sinopsis: Seorang pencuri bernama Scott Lang (Paul Rudd) harus membantu ilmuan sekaligus gurunya yang bernama Dr. Hank Pym (Michael Douglas). Hank telah menciptakan sebuah serum yang dapat membuat tubuh penggunanya mengecil seperti semut.

Then, the next time the application starts, it will recognize the new serial number. The serial number that you purchased is for the use of the software in a specific language, and it will only be accepted by an a product installed in that language. Volume licensing customers cannot purchase from a trial directly, however a volume licensing serial number can be entered in the trial product. After Effect Cs4 Serial Number For Mac bltlly.com/14lnrd. If you purchased your Creative Suite software on a DVD, the serial number for Adobe After Effects CS4 and Adobe Premiere Pro CS4 is inside your box. If you purchased a downloadable version, your serial number was issued to you from the Adobe Store when you purchased. 7b042e0984 Adobe After Effects CS6 Visual Effects and Compositing. Including the Adobe After Effects Classroom. Directly on A-list feature films gave me the. Adobe After Effects CS6 Serial Key Number Free Online 1023-1264-8141-9396-6170-4879 1023-1871-7858-7325-9290-1776 1023-1858-8539-4146-7718-4277. After effect cs4 serial number for mac pro. Download now the serial number for Adobe After Effects CS4. All serial numbers are genuine and you can find more results in our database for Adobe software. Updates are issued periodically and new results might be added for this applications from our community.

Artist: VATitle Of Album: Kaleydo Records Session #30Label: Kaleydo RecordsCatalog#: KLDMX 030Style: Tech HouseDate: 03 August, 2017Quality: 320 kbps / 44100Hz / Joint StereoTracks: 10 + 01 mixedTotal Time: 02:10:12 minSize: 301 mbTrackList:01. Wolves Den - Wave (original mix) 05:0102. Stelmarya - Treasure Island (original mix) 07:0503. Alex Raider - The Ancient Code (original mix) 07:4804. The Sound Alchemyst - Headwork (original mix) 07:0805. Osmyo - Bashlater (original mix) 07:2906. Alex Raider - Justify (Rework 2016) 07:5007.

Stelmarya & Alex Raider - That's When I've Got To Move (original mix) 07:5208. Alex Raider - Crisopea (original mix) 07:0909.

Edgar De Mulder - Machine Gun (original mix) 07:3610. Joe Lukketti - Physical Contact (original mix) 06:1711. Joe Lukketti - Kaleydo Records Session #30 (continuous DJ mix) 58:52.

This set is announced as “The Complete Works” of Edgard Varese, which, in the context of the listed comparisons, is certainly true. Moreover, with the Boulez recordings, made over the period 1977-83, now sounding their age and Nagano’s survey lacking sheer dynamic presence, Chailly sets new standards for an overall collection.‘Complete’ requires clarification. Excluded are the electronic interlude, La procession du Verges, from the 1955 film Around and About Joan Miro (is this still extant?) and the 1947 Etude Varese wrote as preparation for his unrealized Espace project – material from which, according to Chou Wen-Chung, found its way into later works. Successively Varese’s pupil, amanuensis and executor, Professor Chou would appear ideally placed to advise on a project of this nature.

Yet it does seem surprising to omit the Etude, completed, performed and apparently extant, while including Tuning Up, which Varese never realized as such, and Dance for Burgess, which does not exist in a definitive score. That said, the former is an ingenious skit on the orchestral machine, while the latter is an unlikely take on the Broadway dance number: the light they shed on Varese’s preoccupations in the late 1940s makes their inclusion worth while.At two-and-a-half hours’ duration, Varese’s output is similar in length to the mature works of Webern, though more akin to Ruggles in its solitary grandeur.

There now seems little hope of early works being unearthed, as these were most likely destroyed by the composer prior to sailing for New York in 1915. The accidental survival of the song Un grand sommeil noir (a more restrained setting than Ravel’s) offers a glimpse of this pre-history and, in Antony Beaumont’s orchestration, an insight into its likely sound world.In the ensemble pieces from the 1920s and early 1930s, Chailly is responsive not only to dynamic extremes, but also tonal shading. Works such as Octandre and Integrales require scrupulous attention to balance if they are to sound more than crudely aggressive: Chailly secures this without sacrificing physical impact – witness the explosive Hyperprism. He brings out some exquisite harmonic subtleties in Offrandes, Sarah Leonard projecting the texts’ surreal imagery with admirable poise. The fugitive opening bars of Ionisation sound slightly muted in the recorded ambience, though not the cascading tuned percussion towards the close.

The instrumentational problems of Ecuatorial are at last vindicated, allowing Varese’s inspired combination of brass and electronic keyboards to register with awesome power. Chailly opts for the solo bass, but a unison chorus would have heightened the dramatic impact still further.Ameriques, the true intersection of romanticism and modernism, is performed in the original 1921 version, with its even more extravagant orchestral demands and (from 13'36' to 17'48') bizarre reminiscences of The Rite of Spring and Schoenberg’s Five Orchestral Pieces, understandably replaced in the revision (Dohnanyi’s superbly recorded if aloof account makes for illuminating comparison). Arcana was recorded back in 1992: rehearing it confirms that while Chailly lacks Boulez’s implacability, he probes beyond the work’s vast dynamic contours far more deeply than either Mehta or the disappointingly anaemic Slatkin (a reissue of Martinon’s electrifying Chicago reading on RCA, 7/67, is long overdue).No one but Varese has drawn such sustained eloquence from an ensemble of wind and percussion, or invested such emotional power in the primitive electronic medium of the early 1950s. Deserts juxtaposes them in a score which marks the culmination of his search for new means of expression. The opening now seems a poignant evocation of humanity in the atomic age, the ending is resigned but not bitter. The tape interludes in Chailly’s performance have a startling clarity (far superior to what sound like remixes on the Nagano recording, while Boulez omits them entirely), as does the Poeme electronique, Varese’s untypical but exhilarating contribution to the 1958 Brussels World Fair. The unfinished Nocturnal, with its vocal stylizations and belated return of string timbre, demonstrates a continuing vitality that only time could extinguish.Varese has had a significant impact on post-war musical culture, with figures as diverse as Stockhausen, Charlie Parker and Frank Zappa acknowledging his influence.

Chailly’s recordings demonstrate, in unequivocal terms, why this music will continue to provoke and inspire future generations.-More reviews:PERFORMANCE:. / SOUND:. Riccardo Chailly (born 20 February 1953 in Milan) is an Italian conductor.

Chailly studied conducting with Franco Ferrara and became assistant conductor to Claudio Abbado at La Scala at the age of 20. He started his career as an opera conductor and gradually extended his repertoire to encompass symphonic music. Chailly was chief conductor of the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra (1982-1988) and Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (1988-2004). He is currently chief conductor of the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig (since 2005). He recorded exclusively for Decca. Igor Stravinsky (17 June O.S. 5 June 1882 – 6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist, and conductor.

He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the 20th century. He first achieved international fame with three ballets commissioned by the impresario Sergei Diaghilev: The Firebird (1910), Petrushka (1911) and The Rite of Spring (1913). Stravinsky's compositional career was notable for its stylistic diversity. His output is typically divided into three general style periods: a Russian period, a neoclassical period, and a serial period. Riccardo Chailly (born 20 February 1953 in Milan) is an Italian conductor.

Chailly studied conducting with Franco Ferrara and became assistant conductor to Claudio Abbado at La Scala at the age of 20. He started his career as an opera conductor and gradually extended his repertoire to encompass symphonic music. Chailly was chief conductor of the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra (1982-1988) and Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (1988-2004). He is currently chief conductor of the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig (since 2005). He recorded exclusively for Decca.

Artist: VATitle Of Album: Secret Weapons (Summer '17)Label: Fabrique RecordingsCatalog#: FAB127Style: HouseDate: 03 August, 2017Quality: 320 kbps / 44100Hz / Joint StereoTracks: 20Total Time: 01:35:31 minSize: 219 mbTrackList:01. Justin Berger – Been a Long 04:2202. Lykov – Turn It Up Now 04:4003. DJ Favorite – Reach the Sky 03:5904. Richard Highway – Somebody 03:5405.

Hack Jack – I Don’t Wanna 04:5706. Robin Feelgood – Not in Love (Dub Mix) 06:0707.

DJ Kristina Mailana – Ola Ola 04:0708. Lykov – I Can Live 04:3609. Punch Makers – Lose My Mind 05:5410. WDX – Get Away 05:5411.

Lykov – No Break 04:4512. BoysNoise – Get Ready 05:0913. Encarta dictionary free for mac. Lykov – To the Sun (Feat. Murrell) 05:3814. Adriana Johnson – Summer Day 03:4015. DJ Kristina Mailana – Last Night a DJ (Feat.

Maxi Lopez) 04:4716. Lykov – Caring Me 04:5917. DJ Favorite – Rock the Party (DJ Dnk Remix) 03:5018. Going Crazy – I Need You (Club Mix) 04:5719. Lykov – Get Love in the Groove 04:3320.

Will Fast – Touch Me 04:43. Artist: Jacob WillTitle: The Bells & Other Poems by Edgar Allan PoeYear Of Release: 2017Label: Centaur Records, Inc.Genre: ClassicalQuality: flac losslessTotal Time: 00:55:49Total Size: 231 mbTracklist———01. The Bells: No. The Bells: No. 5 Edgar Allan Poe Songs: No.

1, Hear the Sledges with the Bells06. 5 Edgar Allan Poe Songs: No. 2, Evening Star07. 5 Edgar Allan Poe Songs: No.

3, Romance08. 5 Edgar Allan Poe Songs: No. 5 Edgar Allan Poe Songs: No. 5, A Dream Within a DreamThe post appeared first on. Paul’s Cathedral ChoirTitle: Jubilate – 500 Years of Cathedral Music (2017)Year Of Release: 2017Label: DeccaGenre: ClassicalQuality: FLAC (tracks+.cue, booklet)Total Time: 01:15:57Total Size: 337 MBTracklist:1. Paul’s Cathedral Choir, Andrew Carwood, Simon Johnson & Cathedral Choristers of Britain – Coronation Anthem No. 1, HWV 258 'Zadok the Priest' (05:37)2.

Nathaniel Morley, Andrew Carwood, St. Paul’s Cathedral Choir & Simon Johnson – Pt. 1, Hear My Prayer, O God, Incline Thine Ear! Nathaniel Morley, Andrew Carwood, St.

Paul’s Cathedral Choir & Simon Johnson – Pt. 2, O for the Wings of a Dove (05:33)4. Paul’s Cathedral Choir & Andrew Carwood – Justorum Animae, Op.

Paul’s Cathedral Choir & Andrew Carwood – Hosanna to the Son of David (01:57)6. Paul’s Cathedral Choir & Andrew Carwood – Salvator Mundi (03:14)7.

Paul’s Cathedral Choir, Andrew Carwood & Simon Johnson – O God, Thou Art My God, Z. Paul’s Cathedral Choir, Andrew Carwood & Simon Johnson – Lord, Let Me Know Mine End (05:56)9. Paul’s Cathedral Choir, Andrew Carwood & Simon Johnson – Greater Love Hath No Man (06:35)10. Andrew Carwood, St. Paul’s Cathedral Choir & Simon Johnson – O Taste and See (01:46)11. Andrew Carwood, St. Paul’s Cathedral Choir & Simon Johnson – Evening Hymn (06:31)12.

Paul’s Cathedral Choir, Andrew Carwood & Simon Johnson – Jubilate Deo (03:43)13. Paul’s Cathedral Choir, Andrew Carwood & Simon Johnson – The Lord Is My Shepherd (03:05)14. Paul’s Cathedral Choir, Andrew Carwood & Simon Johnson – The Lord Bless You and Keep You (03:05)15.

Paul’s Cathedral Choir, Andrew Carwood & Simon Johnson – Ubi Caritas (04:37)16. Paul’s Cathedral Choir, Andrew Carwood, Simon Johnson & Cathedral Choristers of Britain – A Gaelic Blessing (02:06)17. Paul’s Cathedral Choir, Andrew Carwood, Simon Johnson & Cathedral Choristers of Britain – I Was Glad (07:18)18.

Aled Jones, Andrew Carwood, St. Artist: Trio ViventeTitle: Mayer: Piano Trios & NotturnoYear Of Release: 2017Label: CPOGenre: Classical, Chamber MusicQuality: flac losslessTotal Time: 01:03:12Total Size: 241 mbTracklist———01.

Piano Trio in B Minor, Op. Allegro di molto e con brio – Trio Vivente02. Piano Trio in B Minor, Op. Un poco adagio – Trio Vivente03. Piano Trio in B Minor, Op. Scherzo (Allegro assai) – Trio Vivente04. Piano Trio in B Minor, Op.

Finale (Allegro) – Trio Vivente05. Notturno for Violin & Piano, Op.

48 – Anne Katharina Schreiber06. Piano Trio in D Major, Op.

Andante maestoso – Trio Vivente07. Piano Trio in D Major, Op. Larghetto – Trio Vivente08.

Piano Trio in D Major, Op. Scherzo – Trio Vivente09.

Piano Trio in D Major, Op. Presto – Trio ViventeEmilie Mayer, born in 1812 in Friedland, Mecklenburg, produced an extensive oeuvre in a wide range of musical genres unmatched by any other woman composer of the nineteenth century.

Influenced by her studies with Carl Loewe, she mainly occupied herself with works by Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven and developed a compositional style of her own deliberately following outstanding classical models. In 1850 she organized her first concert exclusively featuring her own compositions at the Berlin Playhouse.

She was able to realize what remained a wish dream for most women composers of her generation: highly acclaimed by the critics, she successfully established herself as a composer. Piano chamber music accounts for the largest share of Emilie Mayer’s oeuvre. The main motive of the first theme of her Piano Trio op.

16 functions as the sole thematic figure and pervades the entire development section, while in her op. 13 she more closely adheres to the classical practices of thematic elaboration. The greater formal freedom of the Notturno forming her last composition and op. 48 offers her the opportunity to move far away from classical formal language. In a loosely connected, practically associative sequence she develops a peacefully flowing narrative from the basic theme initially presented in choral style.

The narrative explores the theme from constantly new angles of vision and develops it in a strongly expressive manner.The post appeared first on. Artist: VATitle Of Album: Ibiza Terrace Deep House Vol.1Label: 4000 Digital RecordsCatalog#: 4DR 036Style: House, Deep HouseDate: 03 August, 2017Quality: 320 kbps / 44100Hz / Joint StereoTracks: 06Total Time: 00:29:24 minSize: 67,99 mbTrackList:01.

Die Fantastische Hubschrauber/Blizzy Gem - Hypnotic Journey (Jason Rivas edit) 08:0102. Jason Rivas/Almost Believers - Tonight, Saint-Tropez (radio edit) 02:5603. Fashion Vampires From Louisiana - Bloody Television (vocal edit) 03:2804. Muzzika Global/Fashion Vampires From Louisiana - Dragonheart 06:2605. Terry De Jeff - Cool Drinks (Jason Rivas Ibiza Terrace mix) 06:2006. Organic Noise From Ibiza - In The Room (DJ Tool Reprise edit) 02:09.

|

Edgard Varèse: Complete Works

Edgard Varèse: Complete Works (two CDs), Decca 460 208-2 or, in USA, London 460 208-2

Until quite recently, even listeners who knew the name of the visionary French/American composer Edgard Varèse had to do some searching if they wanted to hear his music played well. Concert performances were extremely rare, and recordings by no means plentiful.

This was a perplexing situation, considering the expressive force of his music and the pervasiveness of its influence. Frank Zappa, a fervent Varèse admirer, carried some of his ideas into hisown concert music, where they were heard by listeners who had followed Zappa's development from its beginnings in avant-garde rock. The sound of a Varèse instrumental ensemble, with dense, dissonant harmonies in the high woodwinds sustained at high energy above a turbulent, often explosive orchestral texture, has found as firm a place in the musical vocabulary as the iridescent Impressionism of Debussy and Ravel.

Although Varèse was something of a musical iconoclast even during his student days in Paris, it wasn’t until after his arrival in New York in 1916 at age 33 that his radical mature style took shape, and this happened very quickly. Almost all of his previous compositions were destroyed in a Berlin warehouse fire (one survivor, the song, Un grand sommeil noir, included in this set, indicates that they were in a Late Romantic style), but by then he had disowned them and started on an entirely new path. By 1918 he was already working on Amériques, a 25-minute eruption scored for a huge orchestra that included sirens, music that sounded like nothing ever heard before.

|

Even today, Varèse’s remains one of the most original of orchestral styles. It is hard to imagine what the pieces he wrote during the 1920s - the atonal, violently percussive Hyperprism (1922-23) for chamber orchestra, for example, or Arcana for large orchestra - must have sounded like to their original audiences. Some idea can be had from Oscar Thompson’s review in Musical America following the 1927 premiere of Arcana by Leopold Stokowski conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra: “There was no mercy in its disharmony, no pity in its succession of screaming, clashing, clangorous discords […] A series of gunpowder explosions might similarly overawe the ear… ”

But, extreme as these pieces were, they were still only an approximation of the sounds that Varèse wanted to work with. After some further extensions like the famous Ionisation (1931), scored for an ensemble of 13 percussionists playing mostly unpitched instruments and two sirens, and Ecuatorial (1934), whose scoring includes two of the early electronic instruments called ondes-martenots, he composed a solo flute piece, Density 21.5, to fulfill a commission and then found himself unable to complete anything else, abandoning attempt after attempt to create the expressive language of “organized sound”, that he imagined.

It wasn’t until almost two decades later, in 1954, that a new composition by Varèse was heard, but by then he had found what he was looking for. Interspersed into the 25-minute-long Déserts, scored for a percussion- and brass-intensive chamber orchestra are three segments of tape music, or musique concrete, in which Varèse adapts and shapes the recorded sounds of musical instruments, factory machinery, and sonic material from other sources to create an expressive flow that moves in ways remarkably similar to his earlier instrumental music. One of the great technical triumphs of Déserts is the seamlessness with which the orchestral and taped segments connect with each other. Varèse’s next composition after Déserts, Poème Eléctronique, written for the 1958 Brussels World Fair, was created completely on tape.

Little of this music was adequately represented on compact disc until 1990, when Sony Classical issued a remastered version of seven works performed by Pierre Boulez conducting the New York Philharmonic and his own Ensemble InterContemporaine (an earlier Japanese Sony disc that included the chamber orchestra works, released in 1984, had had very limited distribution). The performances were impressive, but the recorded sound of the New York Philharmonic accounts of Amériques and Arcana didn’t do full justice to the complicated orchestral textures of those huge pieces. A few other CDs, most significantly a program on the Nonesuch label of chamber orchestra pieces played by the Contemporary Chamber Ensemble under Arthur Weisberg, were also cherished by those who knew them.

During the musically more adventurous 1960s, much of Varèse’s output was available on LP in excellent performances. At the beginning of that decade Robert Craft, who taught an entire generation how to listen to challenging modern music through his pioneering recordings, introduced this music to many listeners with an LP that collected most of the early chamber orchestra pieces and concluded with the then-new Poème électronique. It was followed by a second disc that astounded its listeners with premiere recordings of Déserts and Arcana. An even better, and so far unequaled, performance of Arcana by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under Jean Martinon was released in 1967 by RCA Victor, and a performance tradition for this music, complemented by an appreciative audience, seemed to be emerging.

But with the collapse of the musical avant-garde during the 1970s the music of Varèse, who had influenced many post-World War II experimental composers, came under a cloud. Recordings disappeared from catalogues, and new ones were few and far between. The Neo-Romantic, Minimalist, and New Age styles that engaged so many composers and listeners were very far from the esthetic of Varèse.

Finally, in the early 1990s, the inevitable reversal began. The re-release on compact disc of the Boulez recordings drew new attention to Varèse’s music, and further re-releases followed, including remastered CDs of Maurice Abravanel’s 1960s premiere recordings of Amériques and Nocturnal and even the original Robert Craft disc, reissued with the original Miro cover art by One-Way Records.

Most encouraging of all were a series of new recordings of major Varèse works by front-rank conductors and orchestras. In 1994 Riccardo Chailly and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra contributed a fine account of Arcana, and in the same year the Cleveland Orchestra under Christoph von Dohnanyi recorded Amériques as part of a CD program that also included Charles Ives’ Fourth Symphony.

The new wave of Varèse recordings has culminated in this 1998 two-CD set of his complete works, superbly performed by Riccardo Chailly conducting two first-class ensembles who understand the music well. The version of Arcana included is the same one that appeared on the 1994 disc, but everything else is new.

“Complete” is a difficult word to use when talking about Varèse’s output. Between 1936 and 1954 he began and abandoned a number of pieces that he later used as raw material for other works. Later in life he composed music to accompany films made by fellow artists, and that work is not represented here. But there is music in this Chailly set that has never been recorded before, and it will probably be new even to devoted admirers of the composer. All of it was made available through the assistance of Professor Chou Wen-chung, a composer who was a close friend and colleague of Varèse’s, and remains the leading authority on his music.

Tuning Up and Dance for Burgess, both recorded here for the first time, are fragments that have been reconstructed and edited by Prof. Chou. The former was composed in 1947 in response to a request by producer Boris Moros for his movie, Carnegie Hall. What Moros wanted was music that suggested the sound of an orchestra tuning up, but what Varèse came up with - a collage of orchestral sound suggesting his earlier music, complete with sirens, as well as material from an abandoned composition called Espace and, at the conclusion, an early version of the music that would form the ending of Déserts - didn’t fit the bill, and was rejected. Chou made the reconstruction heard here from two drafts, and it is not among the composer’s masterpieces.

Dance for Burgess, for chamber orchestra, survives from another failed sojourn into the world of entertainment music. The actor Burgess Meredith, a friend of Varèse’s, was getting ready to act in and direct a musical called Happy as Larry. Meredith requested a short dance for the production, to be choreographed by Anna Sokolow, but the show folded almost immediately and Varèse seems to have forgotten about the music.

Chou resurrects it here, and even in the vivid performance it receives from Chailly and the ASKO Ensemble, it’s hard to imagine who the composer had in mind as an audience for this crazy 1:48-minute scrap. No matter how well you know Varèse’s style, in which jazz is often lurking just under the surface, you’ll probably be caught off-guard by the outburst that begins at 00:28, a perky dance tune scored in the composer’s most strident brass-and-percussion manner. Once again, a trifle, but an appealing one.

Far more substantial is the introduction here of Un grand sommeil noir, a Verlaine setting Varèse wrote in 1906 while he was still studying composition with Charles-Marie Widor at the Paris Conservatoire. Although the style is very much of its turn-of-the-century period, the writing for the voice is full of pre-echoes of Offrandes, a work for soprano and orchestra composed in 1921 in Varèse’s full-blown Modernist manner.

It is performed here twice, first as the original 1906 version for voice and piano, then in Antony Beaumont’s new orchestration, commissioned by Chailly and the Royal Concertgebouw. Beaumont’s appropriately dark realization, despite its percussion-heavy scoring, doesn’t violate the Romantic spirit of the original, but it is far more expansive. It clocks in at 4:08 as compared with 2:46 for the piano/voice version. But for at least one listener, the original is more responsive to the feeling of surrender that saturates the Verlaine text. Mireille Delunsch is a sensitive singer with a rich, creamy soprano voice which she uses skillfully to project the music’s sense of mystery.

For most listeners, the major discovery among the pieces that receive their first recordings here is the original version of Amériques. In his note, Chou explains that, a year after the piece had received its 1926 premiere by Stokowski/Philadelphia, “Varèse prepared a revised version, with a reduction in its mammoth instrumentation, for the first European performance […] in 1929. Published editions of both versions in the 1920s […] were disastrously full of mistakes, most of which were left uncorrected for both concerts. In 1972 I completed a corrected edition of the revision […] Twenty-four years later, in the summer of 1996, I was persuaded by the Decca Record Company Limited to edit Varèse’s manuscript of the original version for performance by the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra under the baton of Riccardo Chailly and recording by Decca.”

Although Chou refers to a reduction of the original orchestration, the impression made on this restored version, to ears accustomed to the 1927 revision, is of greater delicacy. Besides reducing the scoring, Varèse also did some trimming; Chailly takes 24:38 to play the piece, while von Dohnanyi, at roughly the same tempos, gets through it in 21:41 and the old Abravanel takes 22:19.

The restored material includes passages of chamber music-like transparency. There is an extended section after about 14:00 that reveals a tender, reflective aspect of the composer’s artistic personality that rarely surfaces in the revision, or in any of Varèse’s other mature music.

But most of the rest of this astonishing piece fully bears out Prof. Chou’s over-the-top description: […] “a towering tapestry from unimaginable sonic strands. Bursting colors, cascading sonorities, explosive dynamics, swirling rhythms, and thrusting motions coalesce into ever more intense eruptions […]”

Perhaps von Dohnanyi/Cleveland (on Decca 443 172-2) bring a little more abandon to the final pages of the score, but Chailly is much more responsive to the music’s strong sense of wonder.

Superficial similarities in the use of massive forces, dissonant textures, and driving rhythms have led some commentators to write that in his big orchestral pieces, Varèse was imitating the Stravinsky of Le sacre du printemps. Closer listening will reveal that the two were looking in almost opposite directions. Stravinsky was concerned with fertility, and with the tendency of the new to rend and destroy the old as it is being born. Varèse, on the other hand, was interested in something more abstract. He wrote that to him America symbolized “all discoveries, all adventures… the Unknown”, and that he was envisioning “new worlds”. The piece, he said, could just as well have been called “The Himalayas”.

Arcana, Varèse’s other large orchestral piece, was written in 1925-27, after he had composed the series of chamber orchestra pieces that are still his most frequently-performed works. It is less florid, but even more dynamic than Amériques. Once again, the music looks outward for its inspiration: “One star exists, higher than all the rest, ” says a quote from the 16th-century alchemist Paracelsus that Varèse uses as the motto of the score.“ This is the apocalyptic star. The second star is that of the ascendant. The third is that of the elements - of these there are four, so that six stars are established. Besides these there is still another star, imagination, which begets a new star and a new heaven.”

Without a doubt, the power of the creative imagination finds expression in this astonishing piece. Throughout its eighteen minutes, the composer seems to be reaching out for the electronic sounds that would finally become available to him a quarter of a century later. The music moves ahead with irresistible force, propelled by a recurrent lunging motif - Varèse called it an idée fixe - first heard in the opening bars. It moves ahead not by means of any developmental process, but in steps, progressing through a series of sonic blocks until it expends its energy in a sequence of climactic orchestral explosions.

Arcana has been recorded at least nine times, and Chailly’s account is one of the most forceful and persuasive. Among recent versions, it communicates the music’s elemental power far more effectively than either Kent Nagano’s (Erato) or Leonard Slatkin’s (RCA Red Seal) does. But good as it is, it must yield pride of place to Martinon’s Chicago recording, which has just been re-released by RCA Red Seal in its new High Performance series (RCA Red Seal High Performance 09026-63315-2). Just as Mozart intended that his piano concertos should “flow like oil”, Varèse wanted his music to “explode into space”, and under Martinon’s direction, it does just that.

Calling pieces like Intégrales and Octandre “chamber orchestra works ” can give a misleading impression. The sheer weight of their sound creates the illusion of much larger forces than those indicated in the score. Octandre is a wind octet, but its carefully constructed, dissonant chords, built up in strata, give an impression of monumentality that suggests orchestral dimensions.

The ASKO Ensemble strike a balance of ruggedness of sound and precision of execution that serves this music very well. There should be a feeling of rawness of sound, and of great weight being shifted, in the playing of a piece like Intégrales or Hyperprism, and Chailly and his ASKO musicians realize it as successfully as any ensemble to have recorded this music to date.

Jacques Zoon’s rendition of the solo flute piece, Density 21.5, commissioned by flautist George Berrère for performance on his platinum flute, sustains the lyrical flow of the music by resisting the temptation to showcase its unconventional features, like the key-tapping percussive effect that Varèse asks for at one point.

For at least this listener, the all-percussion Ionisation still comes off best in the old Robert Craft recording. As recorded sound it can’t compare with this new version or any of half-a-dozen others recorded during the 1960s and 1970s. But Craft takes it at a quicker tempo than anyone else, and finds an element of joy in the music that no other conductor has brought across in a recording. This new ASKO Ensemble performance is convincing in its somewhat heavier view of the piece, however, and the recorded sound is terrific.

Ecuatorial, a setting of a prayer from the Popol Vuh, is given a knockout performance here by an instrumental ensemble that includes four trumpets, four trombones, and six percussionists as well as two electronic instruments that combine the characteristics of ondes-martenots and theremins. But Chailly opts for Varèse’s original assignment of the vocal part to a baritone soloist. Kevin Deas sings with real intensity, but Boulez’s account, which uses a unison male chorus, draws out even more of the music’s power.

|

Finally, the electronic music. Chailly’s recording here of Déserts supercedes all others, even the outstanding version that the Group for Contemporary Music at Columbia University once recorded for the CRI label. The deserts of the title are, like the America of Amérique, not geographical but spiritual, and the ASKO Ensemble achieve exactly the feeling of emptiness, remoteness, loneliness, that this beautiful piece distils. The tape music intervals (provided by the Columbia University Computer Music Center) have been cleansed of the hiss that almost overwhelmed them in some earlier recordings, and the joints between the organized sound and the live music are more imperceptible than ever.

The original tape for Poème électronique has also undergone some processing. According to a credit in the CD program notes, the version heard here is a “transfer from the original master by Konrad Boehmer and Kees Tazelar, Institute of Sonology, Royal Conservatory” in The Hague. But here there are details that differ significantly from what is heard in the old CBS recording on the Craft disc. The tape hiss is gone, but so is some of the resonance which seemed, in the earlier recording, to have an expressive purpose in the music. The clicks at 00:16, for example, had a halo of resonance around them in the old recording that is completely gone now, arguably to the detriment of the music. But was this new transfer closer to what was heard when Poème électronique was first played through the 400 speakers at Le Corbusier’s Philips Pavilion in Brussels?

Perhaps this set of recordings will remind listeners that Varèse was one of the century’s greatest and most original creative artists. During recent decades, when more soothing and comfortable music than his has been in fashion, he has often been dismissed as a kind of laboratory scientist working with sounds instead of chemicals. But as these performances show, his range was as great as his ambition, and musicians will still be learning from his discoveries for a long time to come.

Sinopsis: Seorang pencuri bernama Scott Lang (Paul Rudd) harus membantu ilmuan sekaligus gurunya yang bernama Dr. Hank Pym (Michael Douglas). Hank telah menciptakan sebuah serum yang dapat membuat tubuh penggunanya mengecil seperti semut.

Then, the next time the application starts, it will recognize the new serial number. The serial number that you purchased is for the use of the software in a specific language, and it will only be accepted by an a product installed in that language. Volume licensing customers cannot purchase from a trial directly, however a volume licensing serial number can be entered in the trial product. After Effect Cs4 Serial Number For Mac bltlly.com/14lnrd. If you purchased your Creative Suite software on a DVD, the serial number for Adobe After Effects CS4 and Adobe Premiere Pro CS4 is inside your box. If you purchased a downloadable version, your serial number was issued to you from the Adobe Store when you purchased. 7b042e0984 Adobe After Effects CS6 Visual Effects and Compositing. Including the Adobe After Effects Classroom. Directly on A-list feature films gave me the. Adobe After Effects CS6 Serial Key Number Free Online 1023-1264-8141-9396-6170-4879 1023-1871-7858-7325-9290-1776 1023-1858-8539-4146-7718-4277. After effect cs4 serial number for mac pro. Download now the serial number for Adobe After Effects CS4. All serial numbers are genuine and you can find more results in our database for Adobe software. Updates are issued periodically and new results might be added for this applications from our community.

Artist: VATitle Of Album: Kaleydo Records Session #30Label: Kaleydo RecordsCatalog#: KLDMX 030Style: Tech HouseDate: 03 August, 2017Quality: 320 kbps / 44100Hz / Joint StereoTracks: 10 + 01 mixedTotal Time: 02:10:12 minSize: 301 mbTrackList:01. Wolves Den - Wave (original mix) 05:0102. Stelmarya - Treasure Island (original mix) 07:0503. Alex Raider - The Ancient Code (original mix) 07:4804. The Sound Alchemyst - Headwork (original mix) 07:0805. Osmyo - Bashlater (original mix) 07:2906. Alex Raider - Justify (Rework 2016) 07:5007.

Stelmarya & Alex Raider - That\'s When I\'ve Got To Move (original mix) 07:5208. Alex Raider - Crisopea (original mix) 07:0909.

Edgar De Mulder - Machine Gun (original mix) 07:3610. Joe Lukketti - Physical Contact (original mix) 06:1711. Joe Lukketti - Kaleydo Records Session #30 (continuous DJ mix) 58:52.

This set is announced as “The Complete Works” of Edgard Varese, which, in the context of the listed comparisons, is certainly true. Moreover, with the Boulez recordings, made over the period 1977-83, now sounding their age and Nagano’s survey lacking sheer dynamic presence, Chailly sets new standards for an overall collection.‘Complete’ requires clarification. Excluded are the electronic interlude, La procession du Verges, from the 1955 film Around and About Joan Miro (is this still extant?) and the 1947 Etude Varese wrote as preparation for his unrealized Espace project – material from which, according to Chou Wen-Chung, found its way into later works. Successively Varese’s pupil, amanuensis and executor, Professor Chou would appear ideally placed to advise on a project of this nature.

Yet it does seem surprising to omit the Etude, completed, performed and apparently extant, while including Tuning Up, which Varese never realized as such, and Dance for Burgess, which does not exist in a definitive score. That said, the former is an ingenious skit on the orchestral machine, while the latter is an unlikely take on the Broadway dance number: the light they shed on Varese’s preoccupations in the late 1940s makes their inclusion worth while.At two-and-a-half hours’ duration, Varese’s output is similar in length to the mature works of Webern, though more akin to Ruggles in its solitary grandeur.

There now seems little hope of early works being unearthed, as these were most likely destroyed by the composer prior to sailing for New York in 1915. The accidental survival of the song Un grand sommeil noir (a more restrained setting than Ravel’s) offers a glimpse of this pre-history and, in Antony Beaumont’s orchestration, an insight into its likely sound world.In the ensemble pieces from the 1920s and early 1930s, Chailly is responsive not only to dynamic extremes, but also tonal shading. Works such as Octandre and Integrales require scrupulous attention to balance if they are to sound more than crudely aggressive: Chailly secures this without sacrificing physical impact – witness the explosive Hyperprism. He brings out some exquisite harmonic subtleties in Offrandes, Sarah Leonard projecting the texts’ surreal imagery with admirable poise. The fugitive opening bars of Ionisation sound slightly muted in the recorded ambience, though not the cascading tuned percussion towards the close.

The instrumentational problems of Ecuatorial are at last vindicated, allowing Varese’s inspired combination of brass and electronic keyboards to register with awesome power. Chailly opts for the solo bass, but a unison chorus would have heightened the dramatic impact still further.Ameriques, the true intersection of romanticism and modernism, is performed in the original 1921 version, with its even more extravagant orchestral demands and (from 13\'36\' to 17\'48\') bizarre reminiscences of The Rite of Spring and Schoenberg’s Five Orchestral Pieces, understandably replaced in the revision (Dohnanyi’s superbly recorded if aloof account makes for illuminating comparison). Arcana was recorded back in 1992: rehearing it confirms that while Chailly lacks Boulez’s implacability, he probes beyond the work’s vast dynamic contours far more deeply than either Mehta or the disappointingly anaemic Slatkin (a reissue of Martinon’s electrifying Chicago reading on RCA, 7/67, is long overdue).No one but Varese has drawn such sustained eloquence from an ensemble of wind and percussion, or invested such emotional power in the primitive electronic medium of the early 1950s. Deserts juxtaposes them in a score which marks the culmination of his search for new means of expression. The opening now seems a poignant evocation of humanity in the atomic age, the ending is resigned but not bitter. The tape interludes in Chailly’s performance have a startling clarity (far superior to what sound like remixes on the Nagano recording, while Boulez omits them entirely), as does the Poeme electronique, Varese’s untypical but exhilarating contribution to the 1958 Brussels World Fair. The unfinished Nocturnal, with its vocal stylizations and belated return of string timbre, demonstrates a continuing vitality that only time could extinguish.Varese has had a significant impact on post-war musical culture, with figures as diverse as Stockhausen, Charlie Parker and Frank Zappa acknowledging his influence.

Chailly’s recordings demonstrate, in unequivocal terms, why this music will continue to provoke and inspire future generations.-More reviews:PERFORMANCE:. / SOUND:. Riccardo Chailly (born 20 February 1953 in Milan) is an Italian conductor.

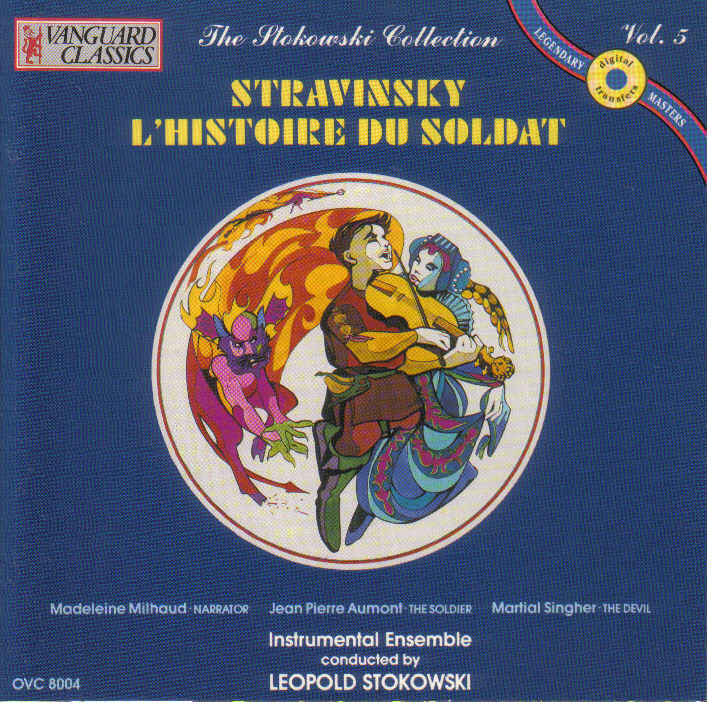

Chailly studied conducting with Franco Ferrara and became assistant conductor to Claudio Abbado at La Scala at the age of 20. He started his career as an opera conductor and gradually extended his repertoire to encompass symphonic music. Chailly was chief conductor of the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra (1982-1988) and Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (1988-2004). He is currently chief conductor of the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig (since 2005). He recorded exclusively for Decca. Igor Stravinsky (17 June O.S. 5 June 1882 – 6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist, and conductor.

He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the 20th century. He first achieved international fame with three ballets commissioned by the impresario Sergei Diaghilev: The Firebird (1910), Petrushka (1911) and The Rite of Spring (1913). Stravinsky\'s compositional career was notable for its stylistic diversity. His output is typically divided into three general style periods: a Russian period, a neoclassical period, and a serial period. Riccardo Chailly (born 20 February 1953 in Milan) is an Italian conductor.

Chailly studied conducting with Franco Ferrara and became assistant conductor to Claudio Abbado at La Scala at the age of 20. He started his career as an opera conductor and gradually extended his repertoire to encompass symphonic music. Chailly was chief conductor of the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra (1982-1988) and Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (1988-2004). He is currently chief conductor of the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig (since 2005). He recorded exclusively for Decca.

Artist: VATitle Of Album: Secret Weapons (Summer \'17)Label: Fabrique RecordingsCatalog#: FAB127Style: HouseDate: 03 August, 2017Quality: 320 kbps / 44100Hz / Joint StereoTracks: 20Total Time: 01:35:31 minSize: 219 mbTrackList:01. Justin Berger – Been a Long 04:2202. Lykov – Turn It Up Now 04:4003. DJ Favorite – Reach the Sky 03:5904. Richard Highway – Somebody 03:5405.

Hack Jack – I Don’t Wanna 04:5706. Robin Feelgood – Not in Love (Dub Mix) 06:0707.

DJ Kristina Mailana – Ola Ola 04:0708. Lykov – I Can Live 04:3609. Punch Makers – Lose My Mind 05:5410. WDX – Get Away 05:5411.

Lykov – No Break 04:4512. BoysNoise – Get Ready 05:0913. Encarta dictionary free for mac. Lykov – To the Sun (Feat. Murrell) 05:3814. Adriana Johnson – Summer Day 03:4015. DJ Kristina Mailana – Last Night a DJ (Feat.

Maxi Lopez) 04:4716. Lykov – Caring Me 04:5917. DJ Favorite – Rock the Party (DJ Dnk Remix) 03:5018. Going Crazy – I Need You (Club Mix) 04:5719. Lykov – Get Love in the Groove 04:3320.

Will Fast – Touch Me 04:43. Artist: Jacob WillTitle: The Bells & Other Poems by Edgar Allan PoeYear Of Release: 2017Label: Centaur Records, Inc.Genre: ClassicalQuality: flac losslessTotal Time: 00:55:49Total Size: 231 mbTracklist———01. The Bells: No. The Bells: No. 5 Edgar Allan Poe Songs: No.

1, Hear the Sledges with the Bells06. 5 Edgar Allan Poe Songs: No. 2, Evening Star07. 5 Edgar Allan Poe Songs: No.

3, Romance08. 5 Edgar Allan Poe Songs: No. 5 Edgar Allan Poe Songs: No. 5, A Dream Within a DreamThe post appeared first on. Paul’s Cathedral ChoirTitle: Jubilate – 500 Years of Cathedral Music (2017)Year Of Release: 2017Label: DeccaGenre: ClassicalQuality: FLAC (tracks+.cue, booklet)Total Time: 01:15:57Total Size: 337 MBTracklist:1. Paul’s Cathedral Choir, Andrew Carwood, Simon Johnson & Cathedral Choristers of Britain – Coronation Anthem No. 1, HWV 258 \'Zadok the Priest\' (05:37)2.

Nathaniel Morley, Andrew Carwood, St. Paul’s Cathedral Choir & Simon Johnson – Pt. 1, Hear My Prayer, O God, Incline Thine Ear! Nathaniel Morley, Andrew Carwood, St.

Paul’s Cathedral Choir & Simon Johnson – Pt. 2, O for the Wings of a Dove (05:33)4. Paul’s Cathedral Choir & Andrew Carwood – Justorum Animae, Op.

Paul’s Cathedral Choir & Andrew Carwood – Hosanna to the Son of David (01:57)6. Paul’s Cathedral Choir & Andrew Carwood – Salvator Mundi (03:14)7.

Paul’s Cathedral Choir, Andrew Carwood & Simon Johnson – O God, Thou Art My God, Z. Paul’s Cathedral Choir, Andrew Carwood & Simon Johnson – Lord, Let Me Know Mine End (05:56)9. Paul’s Cathedral Choir, Andrew Carwood & Simon Johnson – Greater Love Hath No Man (06:35)10. Andrew Carwood, St. Paul’s Cathedral Choir & Simon Johnson – O Taste and See (01:46)11. Andrew Carwood, St. Paul’s Cathedral Choir & Simon Johnson – Evening Hymn (06:31)12.

Paul’s Cathedral Choir, Andrew Carwood & Simon Johnson – Jubilate Deo (03:43)13. Paul’s Cathedral Choir, Andrew Carwood & Simon Johnson – The Lord Is My Shepherd (03:05)14. Paul’s Cathedral Choir, Andrew Carwood & Simon Johnson – The Lord Bless You and Keep You (03:05)15.

Paul’s Cathedral Choir, Andrew Carwood & Simon Johnson – Ubi Caritas (04:37)16. Paul’s Cathedral Choir, Andrew Carwood, Simon Johnson & Cathedral Choristers of Britain – A Gaelic Blessing (02:06)17. Paul’s Cathedral Choir, Andrew Carwood, Simon Johnson & Cathedral Choristers of Britain – I Was Glad (07:18)18.

Aled Jones, Andrew Carwood, St. Artist: Trio ViventeTitle: Mayer: Piano Trios & NotturnoYear Of Release: 2017Label: CPOGenre: Classical, Chamber MusicQuality: flac losslessTotal Time: 01:03:12Total Size: 241 mbTracklist———01.

Piano Trio in B Minor, Op. Allegro di molto e con brio – Trio Vivente02. Piano Trio in B Minor, Op. Un poco adagio – Trio Vivente03. Piano Trio in B Minor, Op. Scherzo (Allegro assai) – Trio Vivente04. Piano Trio in B Minor, Op.

Finale (Allegro) – Trio Vivente05. Notturno for Violin & Piano, Op.

48 – Anne Katharina Schreiber06. Piano Trio in D Major, Op.

Andante maestoso – Trio Vivente07. Piano Trio in D Major, Op. Larghetto – Trio Vivente08.

Piano Trio in D Major, Op. Scherzo – Trio Vivente09.

Piano Trio in D Major, Op. Presto – Trio ViventeEmilie Mayer, born in 1812 in Friedland, Mecklenburg, produced an extensive oeuvre in a wide range of musical genres unmatched by any other woman composer of the nineteenth century.

Influenced by her studies with Carl Loewe, she mainly occupied herself with works by Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven and developed a compositional style of her own deliberately following outstanding classical models. In 1850 she organized her first concert exclusively featuring her own compositions at the Berlin Playhouse.

She was able to realize what remained a wish dream for most women composers of her generation: highly acclaimed by the critics, she successfully established herself as a composer. Piano chamber music accounts for the largest share of Emilie Mayer’s oeuvre. The main motive of the first theme of her Piano Trio op.

16 functions as the sole thematic figure and pervades the entire development section, while in her op. 13 she more closely adheres to the classical practices of thematic elaboration. The greater formal freedom of the Notturno forming her last composition and op. 48 offers her the opportunity to move far away from classical formal language. In a loosely connected, practically associative sequence she develops a peacefully flowing narrative from the basic theme initially presented in choral style.

The narrative explores the theme from constantly new angles of vision and develops it in a strongly expressive manner.The post appeared first on. Artist: VATitle Of Album: Ibiza Terrace Deep House Vol.1Label: 4000 Digital RecordsCatalog#: 4DR 036Style: House, Deep HouseDate: 03 August, 2017Quality: 320 kbps / 44100Hz / Joint StereoTracks: 06Total Time: 00:29:24 minSize: 67,99 mbTrackList:01.

Die Fantastische Hubschrauber/Blizzy Gem - Hypnotic Journey (Jason Rivas edit) 08:0102. Jason Rivas/Almost Believers - Tonight, Saint-Tropez (radio edit) 02:5603. Fashion Vampires From Louisiana - Bloody Television (vocal edit) 03:2804. Muzzika Global/Fashion Vampires From Louisiana - Dragonheart 06:2605. Terry De Jeff - Cool Drinks (Jason Rivas Ibiza Terrace mix) 06:2006. Organic Noise From Ibiza - In The Room (DJ Tool Reprise edit) 02:09.

|

Edgard Varèse: Complete Works

Edgard Varèse: Complete Works (two CDs), Decca 460 208-2 or, in USA, London 460 208-2

Until quite recently, even listeners who knew the name of the visionary French/American composer Edgard Varèse had to do some searching if they wanted to hear his music played well. Concert performances were extremely rare, and recordings by no means plentiful.

This was a perplexing situation, considering the expressive force of his music and the pervasiveness of its influence. Frank Zappa, a fervent Varèse admirer, carried some of his ideas into hisown concert music, where they were heard by listeners who had followed Zappa\'s development from its beginnings in avant-garde rock. The sound of a Varèse instrumental ensemble, with dense, dissonant harmonies in the high woodwinds sustained at high energy above a turbulent, often explosive orchestral texture, has found as firm a place in the musical vocabulary as the iridescent Impressionism of Debussy and Ravel.

Although Varèse was something of a musical iconoclast even during his student days in Paris, it wasn’t until after his arrival in New York in 1916 at age 33 that his radical mature style took shape, and this happened very quickly. Almost all of his previous compositions were destroyed in a Berlin warehouse fire (one survivor, the song, Un grand sommeil noir, included in this set, indicates that they were in a Late Romantic style), but by then he had disowned them and started on an entirely new path. By 1918 he was already working on Amériques, a 25-minute eruption scored for a huge orchestra that included sirens, music that sounded like nothing ever heard before.

|

Even today, Varèse’s remains one of the most original of orchestral styles. It is hard to imagine what the pieces he wrote during the 1920s - the atonal, violently percussive Hyperprism (1922-23) for chamber orchestra, for example, or Arcana for large orchestra - must have sounded like to their original audiences. Some idea can be had from Oscar Thompson’s review in Musical America following the 1927 premiere of Arcana by Leopold Stokowski conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra: “There was no mercy in its disharmony, no pity in its succession of screaming, clashing, clangorous discords […] A series of gunpowder explosions might similarly overawe the ear… ”

But, extreme as these pieces were, they were still only an approximation of the sounds that Varèse wanted to work with. After some further extensions like the famous Ionisation (1931), scored for an ensemble of 13 percussionists playing mostly unpitched instruments and two sirens, and Ecuatorial (1934), whose scoring includes two of the early electronic instruments called ondes-martenots, he composed a solo flute piece, Density 21.5, to fulfill a commission and then found himself unable to complete anything else, abandoning attempt after attempt to create the expressive language of “organized sound”, that he imagined.

It wasn’t until almost two decades later, in 1954, that a new composition by Varèse was heard, but by then he had found what he was looking for. Interspersed into the 25-minute-long Déserts, scored for a percussion- and brass-intensive chamber orchestra are three segments of tape music, or musique concrete, in which Varèse adapts and shapes the recorded sounds of musical instruments, factory machinery, and sonic material from other sources to create an expressive flow that moves in ways remarkably similar to his earlier instrumental music. One of the great technical triumphs of Déserts is the seamlessness with which the orchestral and taped segments connect with each other. Varèse’s next composition after Déserts, Poème Eléctronique, written for the 1958 Brussels World Fair, was created completely on tape.

Little of this music was adequately represented on compact disc until 1990, when Sony Classical issued a remastered version of seven works performed by Pierre Boulez conducting the New York Philharmonic and his own Ensemble InterContemporaine (an earlier Japanese Sony disc that included the chamber orchestra works, released in 1984, had had very limited distribution). The performances were impressive, but the recorded sound of the New York Philharmonic accounts of Amériques and Arcana didn’t do full justice to the complicated orchestral textures of those huge pieces. A few other CDs, most significantly a program on the Nonesuch label of chamber orchestra pieces played by the Contemporary Chamber Ensemble under Arthur Weisberg, were also cherished by those who knew them.

During the musically more adventurous 1960s, much of Varèse’s output was available on LP in excellent performances. At the beginning of that decade Robert Craft, who taught an entire generation how to listen to challenging modern music through his pioneering recordings, introduced this music to many listeners with an LP that collected most of the early chamber orchestra pieces and concluded with the then-new Poème électronique. It was followed by a second disc that astounded its listeners with premiere recordings of Déserts and Arcana. An even better, and so far unequaled, performance of Arcana by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under Jean Martinon was released in 1967 by RCA Victor, and a performance tradition for this music, complemented by an appreciative audience, seemed to be emerging.

But with the collapse of the musical avant-garde during the 1970s the music of Varèse, who had influenced many post-World War II experimental composers, came under a cloud. Recordings disappeared from catalogues, and new ones were few and far between. The Neo-Romantic, Minimalist, and New Age styles that engaged so many composers and listeners were very far from the esthetic of Varèse.

Finally, in the early 1990s, the inevitable reversal began. The re-release on compact disc of the Boulez recordings drew new attention to Varèse’s music, and further re-releases followed, including remastered CDs of Maurice Abravanel’s 1960s premiere recordings of Amériques and Nocturnal and even the original Robert Craft disc, reissued with the original Miro cover art by One-Way Records.

Most encouraging of all were a series of new recordings of major Varèse works by front-rank conductors and orchestras. In 1994 Riccardo Chailly and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra contributed a fine account of Arcana, and in the same year the Cleveland Orchestra under Christoph von Dohnanyi recorded Amériques as part of a CD program that also included Charles Ives’ Fourth Symphony.

The new wave of Varèse recordings has culminated in this 1998 two-CD set of his complete works, superbly performed by Riccardo Chailly conducting two first-class ensembles who understand the music well. The version of Arcana included is the same one that appeared on the 1994 disc, but everything else is new.

“Complete” is a difficult word to use when talking about Varèse’s output. Between 1936 and 1954 he began and abandoned a number of pieces that he later used as raw material for other works. Later in life he composed music to accompany films made by fellow artists, and that work is not represented here. But there is music in this Chailly set that has never been recorded before, and it will probably be new even to devoted admirers of the composer. All of it was made available through the assistance of Professor Chou Wen-chung, a composer who was a close friend and colleague of Varèse’s, and remains the leading authority on his music.

Tuning Up and Dance for Burgess, both recorded here for the first time, are fragments that have been reconstructed and edited by Prof. Chou. The former was composed in 1947 in response to a request by producer Boris Moros for his movie, Carnegie Hall. What Moros wanted was music that suggested the sound of an orchestra tuning up, but what Varèse came up with - a collage of orchestral sound suggesting his earlier music, complete with sirens, as well as material from an abandoned composition called Espace and, at the conclusion, an early version of the music that would form the ending of Déserts - didn’t fit the bill, and was rejected. Chou made the reconstruction heard here from two drafts, and it is not among the composer’s masterpieces.

Dance for Burgess, for chamber orchestra, survives from another failed sojourn into the world of entertainment music. The actor Burgess Meredith, a friend of Varèse’s, was getting ready to act in and direct a musical called Happy as Larry. Meredith requested a short dance for the production, to be choreographed by Anna Sokolow, but the show folded almost immediately and Varèse seems to have forgotten about the music.

Chou resurrects it here, and even in the vivid performance it receives from Chailly and the ASKO Ensemble, it’s hard to imagine who the composer had in mind as an audience for this crazy 1:48-minute scrap. No matter how well you know Varèse’s style, in which jazz is often lurking just under the surface, you’ll probably be caught off-guard by the outburst that begins at 00:28, a perky dance tune scored in the composer’s most strident brass-and-percussion manner. Once again, a trifle, but an appealing one.

Far more substantial is the introduction here of Un grand sommeil noir, a Verlaine setting Varèse wrote in 1906 while he was still studying composition with Charles-Marie Widor at the Paris Conservatoire. Although the style is very much of its turn-of-the-century period, the writing for the voice is full of pre-echoes of Offrandes, a work for soprano and orchestra composed in 1921 in Varèse’s full-blown Modernist manner.

It is performed here twice, first as the original 1906 version for voice and piano, then in Antony Beaumont’s new orchestration, commissioned by Chailly and the Royal Concertgebouw. Beaumont’s appropriately dark realization, despite its percussion-heavy scoring, doesn’t violate the Romantic spirit of the original, but it is far more expansive. It clocks in at 4:08 as compared with 2:46 for the piano/voice version. But for at least one listener, the original is more responsive to the feeling of surrender that saturates the Verlaine text. Mireille Delunsch is a sensitive singer with a rich, creamy soprano voice which she uses skillfully to project the music’s sense of mystery.

For most listeners, the major discovery among the pieces that receive their first recordings here is the original version of Amériques. In his note, Chou explains that, a year after the piece had received its 1926 premiere by Stokowski/Philadelphia, “Varèse prepared a revised version, with a reduction in its mammoth instrumentation, for the first European performance […] in 1929. Published editions of both versions in the 1920s […] were disastrously full of mistakes, most of which were left uncorrected for both concerts. In 1972 I completed a corrected edition of the revision […] Twenty-four years later, in the summer of 1996, I was persuaded by the Decca Record Company Limited to edit Varèse’s manuscript of the original version for performance by the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra under the baton of Riccardo Chailly and recording by Decca.”

Although Chou refers to a reduction of the original orchestration, the impression made on this restored version, to ears accustomed to the 1927 revision, is of greater delicacy. Besides reducing the scoring, Varèse also did some trimming; Chailly takes 24:38 to play the piece, while von Dohnanyi, at roughly the same tempos, gets through it in 21:41 and the old Abravanel takes 22:19.

The restored material includes passages of chamber music-like transparency. There is an extended section after about 14:00 that reveals a tender, reflective aspect of the composer’s artistic personality that rarely surfaces in the revision, or in any of Varèse’s other mature music.

But most of the rest of this astonishing piece fully bears out Prof. Chou’s over-the-top description: […] “a towering tapestry from unimaginable sonic strands. Bursting colors, cascading sonorities, explosive dynamics, swirling rhythms, and thrusting motions coalesce into ever more intense eruptions […]”

Perhaps von Dohnanyi/Cleveland (on Decca 443 172-2) bring a little more abandon to the final pages of the score, but Chailly is much more responsive to the music’s strong sense of wonder.

Superficial similarities in the use of massive forces, dissonant textures, and driving rhythms have led some commentators to write that in his big orchestral pieces, Varèse was imitating the Stravinsky of Le sacre du printemps. Closer listening will reveal that the two were looking in almost opposite directions. Stravinsky was concerned with fertility, and with the tendency of the new to rend and destroy the old as it is being born. Varèse, on the other hand, was interested in something more abstract. He wrote that to him America symbolized “all discoveries, all adventures… the Unknown”, and that he was envisioning “new worlds”. The piece, he said, could just as well have been called “The Himalayas”.

Arcana, Varèse’s other large orchestral piece, was written in 1925-27, after he had composed the series of chamber orchestra pieces that are still his most frequently-performed works. It is less florid, but even more dynamic than Amériques. Once again, the music looks outward for its inspiration: “One star exists, higher than all the rest, ” says a quote from the 16th-century alchemist Paracelsus that Varèse uses as the motto of the score.“ This is the apocalyptic star. The second star is that of the ascendant. The third is that of the elements - of these there are four, so that six stars are established. Besides these there is still another star, imagination, which begets a new star and a new heaven.”

Without a doubt, the power of the creative imagination finds expression in this astonishing piece. Throughout its eighteen minutes, the composer seems to be reaching out for the electronic sounds that would finally become available to him a quarter of a century later. The music moves ahead with irresistible force, propelled by a recurrent lunging motif - Varèse called it an idée fixe - first heard in the opening bars. It moves ahead not by means of any developmental process, but in steps, progressing through a series of sonic blocks until it expends its energy in a sequence of climactic orchestral explosions.

Arcana has been recorded at least nine times, and Chailly’s account is one of the most forceful and persuasive. Among recent versions, it communicates the music’s elemental power far more effectively than either Kent Nagano’s (Erato) or Leonard Slatkin’s (RCA Red Seal) does. But good as it is, it must yield pride of place to Martinon’s Chicago recording, which has just been re-released by RCA Red Seal in its new High Performance series (RCA Red Seal High Performance 09026-63315-2). Just as Mozart intended that his piano concertos should “flow like oil”, Varèse wanted his music to “explode into space”, and under Martinon’s direction, it does just that.

Calling pieces like Intégrales and Octandre “chamber orchestra works ” can give a misleading impression. The sheer weight of their sound creates the illusion of much larger forces than those indicated in the score. Octandre is a wind octet, but its carefully constructed, dissonant chords, built up in strata, give an impression of monumentality that suggests orchestral dimensions.

The ASKO Ensemble strike a balance of ruggedness of sound and precision of execution that serves this music very well. There should be a feeling of rawness of sound, and of great weight being shifted, in the playing of a piece like Intégrales or Hyperprism, and Chailly and his ASKO musicians realize it as successfully as any ensemble to have recorded this music to date.

Jacques Zoon’s rendition of the solo flute piece, Density 21.5, commissioned by flautist George Berrère for performance on his platinum flute, sustains the lyrical flow of the music by resisting the temptation to showcase its unconventional features, like the key-tapping percussive effect that Varèse asks for at one point.

For at least this listener, the all-percussion Ionisation still comes off best in the old Robert Craft recording. As recorded sound it can’t compare with this new version or any of half-a-dozen others recorded during the 1960s and 1970s. But Craft takes it at a quicker tempo than anyone else, and finds an element of joy in the music that no other conductor has brought across in a recording. This new ASKO Ensemble performance is convincing in its somewhat heavier view of the piece, however, and the recorded sound is terrific.

Ecuatorial, a setting of a prayer from the Popol Vuh, is given a knockout performance here by an instrumental ensemble that includes four trumpets, four trombones, and six percussionists as well as two electronic instruments that combine the characteristics of ondes-martenots and theremins. But Chailly opts for Varèse’s original assignment of the vocal part to a baritone soloist. Kevin Deas sings with real intensity, but Boulez’s account, which uses a unison male chorus, draws out even more of the music’s power.

|

Finally, the electronic music. Chailly’s recording here of Déserts supercedes all others, even the outstanding version that the Group for Contemporary Music at Columbia University once recorded for the CRI label. The deserts of the title are, like the America of Amérique, not geographical but spiritual, and the ASKO Ensemble achieve exactly the feeling of emptiness, remoteness, loneliness, that this beautiful piece distils. The tape music intervals (provided by the Columbia University Computer Music Center) have been cleansed of the hiss that almost overwhelmed them in some earlier recordings, and the joints between the organized sound and the live music are more imperceptible than ever.

The original tape for Poème électronique has also undergone some processing. According to a credit in the CD program notes, the version heard here is a “transfer from the original master by Konrad Boehmer and Kees Tazelar, Institute of Sonology, Royal Conservatory” in The Hague. But here there are details that differ significantly from what is heard in the old CBS recording on the Craft disc. The tape hiss is gone, but so is some of the resonance which seemed, in the earlier recording, to have an expressive purpose in the music. The clicks at 00:16, for example, had a halo of resonance around them in the old recording that is completely gone now, arguably to the detriment of the music. But was this new transfer closer to what was heard when Poème électronique was first played through the 400 speakers at Le Corbusier’s Philips Pavilion in Brussels?

Perhaps this set of recordings will remind listeners that Varèse was one of the century’s greatest and most original creative artists. During recent decades, when more soothing and comfortable music than his has been in fashion, he has often been dismissed as a kind of laboratory scientist working with sounds instead of chemicals. But as these performances show, his range was as great as his ambition, and musicians will still be learning from his discoveries for a long time to come.

...'>Edgar Varese Complete Works Rar(29.03.2020)Sinopsis: Seorang pencuri bernama Scott Lang (Paul Rudd) harus membantu ilmuan sekaligus gurunya yang bernama Dr. Hank Pym (Michael Douglas). Hank telah menciptakan sebuah serum yang dapat membuat tubuh penggunanya mengecil seperti semut.

Then, the next time the application starts, it will recognize the new serial number. The serial number that you purchased is for the use of the software in a specific language, and it will only be accepted by an a product installed in that language. Volume licensing customers cannot purchase from a trial directly, however a volume licensing serial number can be entered in the trial product. After Effect Cs4 Serial Number For Mac bltlly.com/14lnrd. If you purchased your Creative Suite software on a DVD, the serial number for Adobe After Effects CS4 and Adobe Premiere Pro CS4 is inside your box. If you purchased a downloadable version, your serial number was issued to you from the Adobe Store when you purchased. 7b042e0984 Adobe After Effects CS6 Visual Effects and Compositing. Including the Adobe After Effects Classroom. Directly on A-list feature films gave me the. Adobe After Effects CS6 Serial Key Number Free Online 1023-1264-8141-9396-6170-4879 1023-1871-7858-7325-9290-1776 1023-1858-8539-4146-7718-4277. After effect cs4 serial number for mac pro. Download now the serial number for Adobe After Effects CS4. All serial numbers are genuine and you can find more results in our database for Adobe software. Updates are issued periodically and new results might be added for this applications from our community.

Artist: VATitle Of Album: Kaleydo Records Session #30Label: Kaleydo RecordsCatalog#: KLDMX 030Style: Tech HouseDate: 03 August, 2017Quality: 320 kbps / 44100Hz / Joint StereoTracks: 10 + 01 mixedTotal Time: 02:10:12 minSize: 301 mbTrackList:01. Wolves Den - Wave (original mix) 05:0102. Stelmarya - Treasure Island (original mix) 07:0503. Alex Raider - The Ancient Code (original mix) 07:4804. The Sound Alchemyst - Headwork (original mix) 07:0805. Osmyo - Bashlater (original mix) 07:2906. Alex Raider - Justify (Rework 2016) 07:5007.

Stelmarya & Alex Raider - That\'s When I\'ve Got To Move (original mix) 07:5208. Alex Raider - Crisopea (original mix) 07:0909.

Edgar De Mulder - Machine Gun (original mix) 07:3610. Joe Lukketti - Physical Contact (original mix) 06:1711. Joe Lukketti - Kaleydo Records Session #30 (continuous DJ mix) 58:52.

This set is announced as “The Complete Works” of Edgard Varese, which, in the context of the listed comparisons, is certainly true. Moreover, with the Boulez recordings, made over the period 1977-83, now sounding their age and Nagano’s survey lacking sheer dynamic presence, Chailly sets new standards for an overall collection.‘Complete’ requires clarification. Excluded are the electronic interlude, La procession du Verges, from the 1955 film Around and About Joan Miro (is this still extant?) and the 1947 Etude Varese wrote as preparation for his unrealized Espace project – material from which, according to Chou Wen-Chung, found its way into later works. Successively Varese’s pupil, amanuensis and executor, Professor Chou would appear ideally placed to advise on a project of this nature.

Yet it does seem surprising to omit the Etude, completed, performed and apparently extant, while including Tuning Up, which Varese never realized as such, and Dance for Burgess, which does not exist in a definitive score. That said, the former is an ingenious skit on the orchestral machine, while the latter is an unlikely take on the Broadway dance number: the light they shed on Varese’s preoccupations in the late 1940s makes their inclusion worth while.At two-and-a-half hours’ duration, Varese’s output is similar in length to the mature works of Webern, though more akin to Ruggles in its solitary grandeur.

There now seems little hope of early works being unearthed, as these were most likely destroyed by the composer prior to sailing for New York in 1915. The accidental survival of the song Un grand sommeil noir (a more restrained setting than Ravel’s) offers a glimpse of this pre-history and, in Antony Beaumont’s orchestration, an insight into its likely sound world.In the ensemble pieces from the 1920s and early 1930s, Chailly is responsive not only to dynamic extremes, but also tonal shading. Works such as Octandre and Integrales require scrupulous attention to balance if they are to sound more than crudely aggressive: Chailly secures this without sacrificing physical impact – witness the explosive Hyperprism. He brings out some exquisite harmonic subtleties in Offrandes, Sarah Leonard projecting the texts’ surreal imagery with admirable poise. The fugitive opening bars of Ionisation sound slightly muted in the recorded ambience, though not the cascading tuned percussion towards the close.

The instrumentational problems of Ecuatorial are at last vindicated, allowing Varese’s inspired combination of brass and electronic keyboards to register with awesome power. Chailly opts for the solo bass, but a unison chorus would have heightened the dramatic impact still further.Ameriques, the true intersection of romanticism and modernism, is performed in the original 1921 version, with its even more extravagant orchestral demands and (from 13\'36\' to 17\'48\') bizarre reminiscences of The Rite of Spring and Schoenberg’s Five Orchestral Pieces, understandably replaced in the revision (Dohnanyi’s superbly recorded if aloof account makes for illuminating comparison). Arcana was recorded back in 1992: rehearing it confirms that while Chailly lacks Boulez’s implacability, he probes beyond the work’s vast dynamic contours far more deeply than either Mehta or the disappointingly anaemic Slatkin (a reissue of Martinon’s electrifying Chicago reading on RCA, 7/67, is long overdue).No one but Varese has drawn such sustained eloquence from an ensemble of wind and percussion, or invested such emotional power in the primitive electronic medium of the early 1950s. Deserts juxtaposes them in a score which marks the culmination of his search for new means of expression. The opening now seems a poignant evocation of humanity in the atomic age, the ending is resigned but not bitter. The tape interludes in Chailly’s performance have a startling clarity (far superior to what sound like remixes on the Nagano recording, while Boulez omits them entirely), as does the Poeme electronique, Varese’s untypical but exhilarating contribution to the 1958 Brussels World Fair. The unfinished Nocturnal, with its vocal stylizations and belated return of string timbre, demonstrates a continuing vitality that only time could extinguish.Varese has had a significant impact on post-war musical culture, with figures as diverse as Stockhausen, Charlie Parker and Frank Zappa acknowledging his influence.

Chailly’s recordings demonstrate, in unequivocal terms, why this music will continue to provoke and inspire future generations.-More reviews:PERFORMANCE:. / SOUND:. Riccardo Chailly (born 20 February 1953 in Milan) is an Italian conductor.

Chailly studied conducting with Franco Ferrara and became assistant conductor to Claudio Abbado at La Scala at the age of 20. He started his career as an opera conductor and gradually extended his repertoire to encompass symphonic music. Chailly was chief conductor of the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra (1982-1988) and Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (1988-2004). He is currently chief conductor of the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig (since 2005). He recorded exclusively for Decca. Igor Stravinsky (17 June O.S. 5 June 1882 – 6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist, and conductor.

He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the 20th century. He first achieved international fame with three ballets commissioned by the impresario Sergei Diaghilev: The Firebird (1910), Petrushka (1911) and The Rite of Spring (1913). Stravinsky\'s compositional career was notable for its stylistic diversity. His output is typically divided into three general style periods: a Russian period, a neoclassical period, and a serial period. Riccardo Chailly (born 20 February 1953 in Milan) is an Italian conductor.

Chailly studied conducting with Franco Ferrara and became assistant conductor to Claudio Abbado at La Scala at the age of 20. He started his career as an opera conductor and gradually extended his repertoire to encompass symphonic music. Chailly was chief conductor of the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra (1982-1988) and Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (1988-2004). He is currently chief conductor of the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig (since 2005). He recorded exclusively for Decca.

Artist: VATitle Of Album: Secret Weapons (Summer \'17)Label: Fabrique RecordingsCatalog#: FAB127Style: HouseDate: 03 August, 2017Quality: 320 kbps / 44100Hz / Joint StereoTracks: 20Total Time: 01:35:31 minSize: 219 mbTrackList:01. Justin Berger – Been a Long 04:2202. Lykov – Turn It Up Now 04:4003. DJ Favorite – Reach the Sky 03:5904. Richard Highway – Somebody 03:5405.

Hack Jack – I Don’t Wanna 04:5706. Robin Feelgood – Not in Love (Dub Mix) 06:0707.

DJ Kristina Mailana – Ola Ola 04:0708. Lykov – I Can Live 04:3609. Punch Makers – Lose My Mind 05:5410. WDX – Get Away 05:5411.

Lykov – No Break 04:4512. BoysNoise – Get Ready 05:0913. Encarta dictionary free for mac. Lykov – To the Sun (Feat. Murrell) 05:3814. Adriana Johnson – Summer Day 03:4015. DJ Kristina Mailana – Last Night a DJ (Feat.

Maxi Lopez) 04:4716. Lykov – Caring Me 04:5917. DJ Favorite – Rock the Party (DJ Dnk Remix) 03:5018. Going Crazy – I Need You (Club Mix) 04:5719. Lykov – Get Love in the Groove 04:3320.

Will Fast – Touch Me 04:43. Artist: Jacob WillTitle: The Bells & Other Poems by Edgar Allan PoeYear Of Release: 2017Label: Centaur Records, Inc.Genre: ClassicalQuality: flac losslessTotal Time: 00:55:49Total Size: 231 mbTracklist———01. The Bells: No. The Bells: No. 5 Edgar Allan Poe Songs: No.

1, Hear the Sledges with the Bells06. 5 Edgar Allan Poe Songs: No. 2, Evening Star07. 5 Edgar Allan Poe Songs: No.

3, Romance08. 5 Edgar Allan Poe Songs: No. 5 Edgar Allan Poe Songs: No. 5, A Dream Within a DreamThe post appeared first on. Paul’s Cathedral ChoirTitle: Jubilate – 500 Years of Cathedral Music (2017)Year Of Release: 2017Label: DeccaGenre: ClassicalQuality: FLAC (tracks+.cue, booklet)Total Time: 01:15:57Total Size: 337 MBTracklist:1. Paul’s Cathedral Choir, Andrew Carwood, Simon Johnson & Cathedral Choristers of Britain – Coronation Anthem No. 1, HWV 258 \'Zadok the Priest\' (05:37)2.